Choking the Back of My Throat Then the Plume Appeared Again the Pyre by the Power of My Will

Selecting a Ghost (sub-titled: The Ghosts of Goresthorpe Grange) is a brusk story written by Arthur Conan Doyle first published in the London Society mag in December 1883. Later published under the following titles: The Secret of Goresthorpe Grange, The Undercover of the Grange.

An earlier text, estimated written effectually 1877, The Haunted Grange of Goresthorpe is another story. It was sent to Blackwood'south Mag and neither published or returned. It is now in the National Library of Scotland with the Blackwood Archives (MS 4791).

Contents

- 1 Editions

- 2 Covers

- 3 Illustrations

- 4 Adaptations

- 4.one Comics

- 4.2 Curt movie

- 5 Plot summary (spoiler)

- 6 Selecting a Ghost

Editions

- in London Order (december 1883 [UK])

- in The New-York Times (23 december 1883 [Usa])

- in Dreamland and Ghostland vol. 3 (october 1887, George Redway [UK])

- in Ghost Stories and Presentiments (november 1888, George Redway [Great britain])

- in Strange Secrets (june 1889, Chatto & Windus) as The Secret of Goresthorpe Grange

- in Mysteries and Adventures (1893, Heinemann and Balestier [DE])

- The Secret of Goresthorpe Grange (1894-1896, George Munro's Sons Library of Popular Novels No. 184 [US])

- in Strange Secrets (1895, R. F. Fenno & Co. [Us]) as The Secret of Goresthorpe Grange

- The Underground of Goresthorpe Grange (1898, George Munro'due south Sons Favorite Series of Popular Novels No. 77 [United states])

- The Secret of Goresthorpe Grange (1898-1899, The American News Co. Favourite Series of Popular Novels No. 77 [U.s.a.])

- in The Secret of Goresthorpe Grange (1900, George Munro'south Sons The Savoy series No. 234 [The states])

- in Foreign Secrets (1906, R. F. Fenno & Co. [The states]) every bit The Hush-hush of Goresthorpe Grange

- in Le Parasite (1909, P.-V. Stock [FR]) as Le Cloak-and-dagger de Goresthorpe Grange

- The Secret of the Grange (1910, Max Stein Atlantic Library No. 46 [US])

- in Le Parasite (ca. 1920-1923, Fifty'Édition Française Illustrée [FR]) as Le Secret de Goresthorpe Grange

- in Dimanche Illustré No. 299 (18 november 1928 [FR]) as Le Marchand de fantômes, i ill. by G. Dutriac

Covers

Illustrations

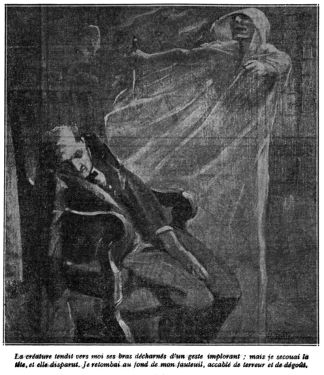

- Illustrations by G. Dutriac in Dimanche Illustré (18 november 1928)

-

The creature stretched out its fleshless arms to me as if in entreaty, but I shook my head; and information technology vanished, leaving a low, sickening, repulsive odour behind it. I sank back in my chair, so overcome by terror and cloy.

Adaptations

Comics

- 2002 : The Ghosts of Goresthorpe Grange, by Tom Pomplun (writer) and Peter Gullerud (fine art)

Curt movie

- 2018 : The Ghost Purchaser

Plot summary (spoiler)

Mr. Silas D'Odd is a rich man who bought a feudal mansion known as Goresthorpe Grange. He enjoys having all the article of furniture plumbing fixtures in a medieval castle: crest, armors, tapestries, ancestors portraits, etc. But in that location is something important missing. A ghost. Fifty-fifty his neighbor, Mr. Jorrocks of Havistock Subcontract, has a ghost. Mr. D'Odd decides to write to his cousin, Jack Brocket, a man able to find anything if information technology can exist sold. After a few days, Jack meets Mr. Abrahams, a human being pretending to take already washed a similar job once or twice. D'Odd immediately invites him to his mansion. This adept-humourous little human explains that ghosts may exist seen at a quarter to ane with the use of a Lucoptolycus potion. When the time has come, Mr. D'Odd drinks the potion and falls in a semi-unconsciousness, starting to meet ghosts... Half a dozen different ones come and innovate themselves to the lanlord. Some are ugly, some scary, murderers, alone souls... Mr. D'Odd chooses the last 1, a beautiful lady with a seraphic smile. After that, he falls asleep because of the drug, but he is soon awakened by his wife yelling they take been robbed. Scotland Yard tells him that the description of Mr. Abrahams corresponds perfectly to Jemmy Wilson, alias The Nottingham Crakster.

Selecting a Ghost

I am certain that Nature never intended me to be a cocky-made human being. There are times when I can hardly bring myself to realise that twenty years of my life were spent behind the counter of a grocer'south store in the East Stop of London, and that information technology was through such an avenue that I reached a wealthy independence and the possession of Goresthorpe Grange. My habits are conservative, and my tastes refined and aristocratic. I have a soul which spurns the vulgar herd. Our family, the D'Odds, appointment back to a prehistoric era, as is to be inferred from the fact that their advent into British history is not commented on by whatever trustworthy historian. Some instinct tells me that the blood of a Crusader runs in my veins. Fifty-fifty now, after the lapse of and then many years, such exclamations as "By'r Lady!" rise naturally to my lips, and I feel that, should circumstances require it, I am capable of rising in my stirrups and dealing an infidel a blow — say with a mace — which would considerably astonish him.

Goresthorpe Grange is a feudal mansion — or so it was termed in the advertisement which originally brought information technology under my notice. Its correct to this describing word had a most remarkable effect upon its price, and the advantages gained may mayhap be more than sentimental than real. Still, it is soothing to me to know that I have slits in my staircase through which I can belch arrows; and at that place is a sense of power in the fact of possessing a complicated apparatus by means of which I am enabled to pour molten atomic number 82 upon the head of the casual company. These things chime in with my peculiar humour, and I exercise not grudge to pay for them. I am proud of my battlements and of the round uncovered sewer which girds me round. I am proud of my portcullis and donjon and go along. There is only one matter wanting to circular off the mediaevalism of my home, and to render information technology symmetrically and completely antique. Goresthorpe Grange is non provided with a ghost.

Any man with onetime-fashioned tastes and ideas as to how such establishments should be conducted, would have been disappointed at the omission. In my case information technology was specially unfortunate. From my babyhood I had been an earnest student of the supernatural, and a firm laic in it. I have revelled in ghostly literature until in that location is hardly a tale bearing upon the subject area which I have not perused. I learned the High german linguistic communication for the sole purpose of mastering a book upon demonology. When an babe I had secreted myself in dark rooms in the hope of seeing some of those bogies with which my nurse used to threaten me; and the aforementioned feeling is equally strong in me now equally so. It was a proud moment when I felt that a ghost was one of the luxuries which coin might command.

It is true that in that location was no mention of an apparition in the advertizing. On reviewing the mildewed walls, however, and the shadowy corridors, I had taken information technology for granted that there was such a thing on the premises. As the presence of a kennel presupposes that of a canis familiaris, so I imagined that it was impossible that such desirable quarters should be untenanted by one or more restless shades. Good heavens, what can the noble family from whom I purchased it have been doing during these hundreds of years! Was there no member of it spirited enough to make away with his sweetheart, or take some other steps calculated to establish a hereditary spectre? Even now I can hardly write with patience upon the subject.

For a long fourth dimension I hoped against hope. Never did rat squeak behind the wainscot, or pelting drip upon the attic flooring, without a wild thrill shooting through me as I thought that at last I had come up upon traces of some unquiet soul. I felt no bear on of fear upon these occasions. If it occurred in the night-time, I would send Mrs. D'Odd — who is a strong-minded woman — to investigate the matter, while I covered up my head with the bedclothes and indulged in an ecstacy of expectation. Alas, the result was ever the same! The suspicious sound would be traced to some cause so absurdly natural and commonplace that the most fervid imagination could not clothe it with whatsoever of the glamour of romance.

I might have reconciled myself to this state of things, had it not been for Jorrocks of Havistock Farm. Jorrocks is a coarse, burly, matter-of-fact fellow, whom I just happened to know through the adventitious circumstance of his fields adjoining my demesne. Yet this human being, though utterly devoid of all appreciation of archaeological unities, is in possession of a well-authenticated and undeniable spectre. Its existence only dates back, I believe, to the reign of the Second George, when a young lady cutting her throat upon hearing of the death of her lover at the battle of Dettingen. Still, fifty-fifty that gives the house an air of respectability, particularly when coupled with blood stains upon the flooring. Jorrocks is densely unconscious of his good fortune; and his language when he reverts to the apparition is painful to listen to. He little dreams how I covet every one of those moans and nocturnal wails which he describes with unnecessary objurgation. Things are indeed coming to a pretty pass when democratic spectres are immune to desert the landed proprietors and counteract every social distinction by taking refuge in the houses of the not bad unrecognised.

I have a large amount of perseverance. Nothing else could take raised me into my rightful sphere, considering the uncongenial temper in which I spent the earlier part of my life. I felt now that a ghost must be secured, but how to set about securing i was more than either Mrs. D'Odd or myself was able to determine. My reading taught me that such phenomena are usually the outcome of criminal offense. What law-breaking was to exist done, so, and who was to practise it? A wild idea entered my mind that Watkins, the firm-steward, might be prevailed upon — for a consideration — to immolate himself or someone else in the interests of the establishment. I put the affair to him in a half-jesting manner; but it did non seem to strike him in a favourable light. The other servants sympathised with him in his opinion — at least, I cannot account in any other style for their having left the firm in a torso the aforementioned afternoon.

"My dear," Mrs. D'Odd remarked to me 1 mean solar day after dinner, equally I sat moodily sipping a cup of sack — I beloved the skilful former names — "my love, that odious ghost of Jorrocks' has been gibbering again."

"Let it gibber!" I answered, recklessly.

Mrs. D'Odd struck a few chords on her virginal and looked thoughtfully into the fire.

"I'll tell you what information technology is, Argentine," she said at last, using the pet name which we usually substituted for Silas, "we must have a ghost sent down from London."

"How tin you be so idiotic, Matilda?" I remarked, severely. "Who could get us such a thing?"

"My cousin, Jack Brocket, could," she answered, confidently.

Now, this cousin of Matilda's was rather a sore bailiwick between united states. He was a rakish, clever young fellow, who had tried his paw at many things, but wanted perseverance to succeed at whatsoever. He was, at that time, in chambers in London, professing to exist a general amanuensis, and really living, to a great extent, upon his wits. Matilda managed then that most of our business should pass through his hands, which certainly saved me a great deal of trouble; but I found that Jack's commission was more often than not considerably larger than all the other items of the pecker put together. Information technology was this fact which fabricated me feel inclined to rebel against whatever further negotiations with the young gentleman.

"O yes, he could," insisted Mrs. D., seeing the look of disapprobation upon my face up. "Yous recollect how well he managed that concern virtually the crest?"

"It was only a resuscitation of the old family coat-of-arms, my dear," I protested.

Matilda smiled in an irritating style. "At that place was a resuscitation of the family portraits, besides, dear," she remarked. "You lot must permit that Jack selected them very judiciously."

I idea of the long line of faces which adorned the walls of my banqueting-hall, from the burly Norman robber, through every gradation of casque, plumage, and ruff, to the sombre Chesterfieldian private who appears to take staggered against a pillar in his agony at the return of a maiden MS. which he grips convulsively in his right manus. I was fain to confess that in that instance he had done his work well, and that it was just fair to give him an order — with the usual committee — for a family unit spectre should such a matter exist accessible.

It is one of my maxims to human action promptly when once my mind is fabricated up. Noon of the adjacent day found me ascending the spiral stone staircase which leads to Mr. Brocket's chambers, and admiring the succession of arrows and fingers upon the whitewashed wall, all indicating the management of that gentleman's sanctum. Every bit it happened, bogus aids of the sort were entirely unnecessary, every bit an blithe flap-dance overhead could proceed from no other quarter, though it was replaced by a deathly silence as I groped my way up the stair. The door was opened past a youth evidently astounded at the advent of a client, and I was ushered into the presence of my young friend, who was writing furiously in a large ledger — upside down, every bit I afterwards discovered.

After the first greetings, I plunged into business at once. "Await here, Jack," I said, "I desire you to become me a spirit, if you lot tin can."

"Spirits you mean!" shouted my married woman's cousin, plunging his hand into the waste-newspaper basket and producing a bottle with the celerity of a conjuring trick. "Let's have a drink!"

I held up my hand equally a mute appeal against such a proceeding so early in the mean solar day; merely on lowering it again I institute that I had about involuntarily closed my fingers round the tumbler which my adviser had pressed upon me. I drank the contents hastily off, lest anyone should come in upon usa and fix me down equally a toper. After all there was something very amusing about the young fellow's eccentricities.

"Not spirits," I explained, smilingly; "an apparition — a ghost. If such a thing is to be had, I should be very willing to negotiate."

"A ghost for Goresthorpe Grange?" inquired Mr. Brocket, with as much coolness as if I had asked for a drawing-room suite.

"Quite then," I answered.

"Easiest thing in the globe," said my companion, filling up my glass again in spite of my remonstrance. "Let united states see!" Here he took downwardly a big red note-book, with all the letters of the alphabet in a fringe down the edge. "A ghost you said, didn't you lot? That's G. Thousand — gems — gimlets — gas-pipes — gauntlets — guns — galleys. Ah, here we are. Ghosts. Volume nine, section six, page forty-one. Excuse me!" And Jack ran up a ladder and began rummaging among the pile of ledgers on a high shelf. I felt half inclined to empty my glass into the spittoon when his back was turned; simply on second thoughts I disposed of it in a legitimate mode.

"Here it is!" cried my London amanuensis, jumping off the ladder with a crash, and depositing an enormous volume of manuscript upon the table. "I have all these things tabulated, so that I may lay my easily upon them in a moment. It's all correct — it's quite weak" (here he filled our glasses over again). "What were we looking upward, over again?"

"Ghosts," I suggested.

"Of course; page 41. Here we are. T.H. Fowler & Son, Dunkel Street, suppliers of mediums to the nobility and gentry; charms sold — beloved philtres — mummies — horoscopes cast.' Naught in your line there, I suppose."

I shook my caput despondently.

"'Frederick Tabb,'" continued my wife's cousin, "'sole aqueduct of communication between the living and the dead. Proprietor of the spirits of Byron, Kirke White, Grimaldi, Tom Cribb, and Inigo Jones.' That's about the figure!"

"Zilch romantic plenty there," I objected. "Skilful heavens! Fancy a ghost with a black eye and a handkerchief tied round its waist, or turning summersaults, and saying, 'How are you tomorrow?'" The very idea made me so warm that I emptied my glass and filled it again.

"Here is another," said my companion, "'Christopher McCarthy; bi-weekly seances — attended past all the eminent spirits of aboriginal and modern times. Nativities — charms — abracadabras, messages from the dead.' He might be able to aid usa. However, I shall have a hunt circular myself to-morrow, and meet some of these fellows. I know their haunts, and information technology's odd if I can't choice up something cheap. So in that location's an cease of business," he concluded, hurling the ledger into the corner, "and now we'll have something to beverage."

We had several things to drink — so many that my inventive faculties were dulled next morning, and I had some niggling difficulty in explaining to Mrs. D'Odd why it was that I hung my boots and spectacles upon a peg along with my other garments earlier retiring to residual. The new hopes excited by the confident manner in which my agent had undertaken the committee, caused me to rising superior to alcoholic reaction, and I paced nigh the rambling corridors and old-fashioned rooms, picturing to myself the appearance of my expected acquisition, and deciding what part of the building would harmonise best with its presence. After much consideration, I pitched upon the banqueting-hall as beingness, on the whole, well-nigh suitable for its reception. It was a long depression room, hung round with valuable tapestry and interesting relics of the old family to whom information technology had belonged. Coats of mail and implements of state of war glimmered fitfully as the light of the fire played over them, and the wind crept under the door, moving the hangings to and fro with a ghastly rustling. At i finish there was the raised belvedere, on which in ancient times the host and his guests used to spread their table, while a descent of a couple of steps led to the lower part of the hall, where the vassals and retainers held wassail. The floor was uncovered by any sort of carpeting, but a layer of rushes had been scattered over it past my management. In the whole room in that location was nothing to remind i of the nineteenth century; except, indeed, my own solid silverish plate, stamped with the resuscitated family artillery, which was laid out upon an oak table in the centre. This, I determined, should be the haunted room, supposing my wife's cousin to succeed in his negotiation with the spirit-mongers. There was nix for it now but to look patiently until I heard some news of the result of his inquiries.

A letter came in the course of a few days, which, if it was brusk, was at least encouraging. Information technology was scribbled in pencil on the back of a playbill, and sealed evidently with a tobacco-stopper. "Am on the rail," information technology said. "Nil of the sort to be had from any professional person spiritualist, but picked up a fellow in a pub yesterday who says he can manage information technology for y'all. Will ship him down unless you wire to the reverse. Abrahams is his name, and he has done ane or ii of these jobs earlier." The alphabetic character wound upwardly with some breathless allusions to a bank check, and was signed by my affectionate cousin, John Brocket.

I need hardly say that I did non wire, but awaited the arrival of Mr. Abrahams with all impatience. In spite of my belief in the supernatural, I could scarcely credit the fact that any mortal could accept such a command over the spirit-earth equally to deal in them and castling them against mere earthly gold. Still, I had Jack's give-and-take for it that such a merchandise existed; and here was a gentleman with a Judaical name set to demonstrate it by proof positive. How vulgar and commonplace Jorrocks' eighteenth-century ghost would announced should I succeed in securing a existent mediaeval apparition! I almost thought that one had been sent down in advance, for, equally I walked round the moat that night earlier retiring to rest, I came upon a dark figure engaged in surveying the machinery of my portcullis and drawbridge. His get-go of surprise, however, and the style in which he hurried off into the darkness, speedily convinced me of his earthly origin, and I put him downward as some admirer of one of my female person retainers mourning over the muddy Hellespont which divided him from his honey. Whoever he may take been, he disappeared and did not return, though I loitered most for some time in the hope of communicable a glimpse of him and exercising my feudal rights upon his person.

Jack Brocket was as good every bit his word. The shades of another evening were beginning to darken round Goresthorpe Grange, when a peal at the outer bong, and the sound of a fly pulling upwardly, announced the inflow of Mr. Abrahams. I hurried down to meet him, one-half expecting to see a option assortment of ghosts crowding in at his rear. Instead, still, of being the sallow-faced, melancholy-eyed man that I had pictured to myself, the ghost-dealer was a sturdy little podgy fellow, with a pair of wonderfully keen sparkling eyes and a mouth which was constantly stretched in a expert-humoured, if somewhat artificial, grin. His sole stock-intrade seemed to consist of a pocket-size leather bag jealously locked and strapped, which emitted a metallic chink upon existence placed on the stone flags in the hall.

"And 'ow are you, sir?" he asked, wringing my mitt with the utmost effusion. "And the missus, 'ow is she? And all the others — 'ow's all their 'ealth?"

I intimated that we were all as well as could reasonably exist expected, simply Mr. Abrahams happened to catch a glimpse of Mrs. D'Odd in the distance, and at once plunged at her with some other cord of inquiries every bit to her health, delivered and so volubly and with such an intense earnestness, that I one-half expected to see him terminate his cross-test by feeling her pulse and enervating a sight of her tongue. All this fourth dimension his little eyes rolled round and circular, shifting perpetually from the floor to the ceiling, and from the ceiling to the walls, taking in apparently every article of piece of furniture in a unmarried comprehensive glance.

Having satisfied himself that neither of united states of america was in a pathological condition, Mr. Abrahams suffered me to lead him upstairs, where a repast had been laid out for him to which he did aplenty justice. The mysterious little handbag he carried along with him, and deposited it under his chair during the meal. It was not until the table had been cleared and we were left together that he broached the matter on which he had come down.

"I hunderstand," he remarked, puffing at a trichinopoly, "that you want my 'elp in fitting up this 'ere 'ouse with a happarition."

I best-selling the definiteness of his surmise, while mentally wondering at those restless eyes of his, which still danced about the room every bit if he were making an inventory of the contents.

"And yous won't observe a better man for the job, though I says it every bit shouldn't," continued my companion. "Wot did I say to the immature gent wot spoke to me in the bar of the Lame Dog? 'Can you do it?' says he. 'Try me,' says I, 'me and my pocketbook. Just attempt me.' I couldn't say fairer than that."

My respect for Jack Brocket's business capacities began to go up very considerably. He certainly seemed to take managed the matter wonderfully well. "You don't mean to say that you carry ghosts near in bags?" I remarked, with diffidence.

Mr. Abrahams smiled a smile of superior knowledge. "You wait," he said; "give me the right place and the right hour, with a piffling of the essence of Lucoptolycus" — hither he produced a small canteen from his waistcoat pocket — "and you lot won't observe no ghost that I ain't up to. You'll encounter them yourself, and pick your own, and I can't say fairer than that."

As all Mr. Abrahams' protestations of fairness were accompanied past a cunning leer and a wink from one or other of his wicked trivial eyes, the impression of candour was somewhat weakened.

"When are you going to do it?" I asked, reverentially.

"Ten minutes to one in the morning time," said Mr. Abrahams, with decision. "Some says midnight, but I says ten to i, when there ain't such a crowd, and y'all tin can option your own ghost. And now," he continued, ascent to his feet, "suppose yous trot me round the premises, and permit me see where you wants information technology; for there's some places as attracts 'em, and some as they won't hear of — not if there was no other place in the globe."

Mr. Abrahams inspected our corridors and chambers with a most critical and observant heart, fingering the one-time tapestry with the air of a connoisseur, and remarking in an undertone that it would "match uncommon overnice." It was not until he reached the banqueting-hall, however, which I had myself picked out, that his admiration reached the pitch of enthusiasm. "'Ere's the identify!" he shouted, dancing, pocketbook in hand, round the tabular array on which my plate was lying, and looking not unlike some quaint lilliputian goblin himself. "'Ere's the place; we won't get nothin' to beat this! A fine room — noble, solid, none of your electro-plate trash! That'due south the way as things ought to exist done, sir. Enough of room for 'em to glide hither. Ship up some brandy and the box of weeds; I'll sit here by the fire and practice the preliminaries, which is more than trouble than yous'd retrieve; for them ghosts carries on hawful at times, before they finds out who they've got to deal with. If you lot was in the room they'd tear you to pieces as similar as not. You leave me alone to tackle them, and at half-past twelve come up in, and I lay they'll exist tranquillity plenty by then."

Mr. Abrahams' request struck me equally a reasonable ane, so I left him with his feet upon the mantelpiece, and his chair in front of the fire, fortifying himself with stimulants against his refractory visitors. From the room beneath, in which I sabbatum with Mrs. D'Odd, I could hear that, after sitting for some time, he rose upward and paced about the hall with quick impatient steps. We and then heard him endeavor the lock of the door, and afterward drag some heavy article of article of furniture in the management of the window, on which, apparently, he mounted, for I heard the creaking of the rusty hinges as the diamond-paned casement folded astern, and I knew it to be situated several anxiety above the trivial man's reach. Mrs. D'Odd says that she could distinguish his vocalization speaking in depression and rapid whispers after this, but that may have been her imagination. I confess that I began to experience more impressed than I had deemed it possible to be. There was something awesome in the thought of the alone mortal standing by the open window and summoning in from the gloom exterior the spirits of the nether earth. It was with a trepidation which I could hardly disguise from Matilda that I observed that the clock was pointing to half-by twelve, and that the time had come for me to share the vigil of my visitor.

He was sitting in his erstwhile position when I entered, and there were no signs of the mysterious movements which I had overheard, though his chubby face up was flushed every bit with recent exertion.

"Are yous succeeding all right?" I asked equally I came in, putting on every bit careless an air as possible, only glancing involuntarily circular the room to see if we were alone.

"Only your assist is needed to consummate the thing," said Mr. Abrahams, in a solemn voice. "Yous shall sit by me and partake of the essence of Lucoptolycus, which removes the scales from our earthly optics. Any yous may chance to 'see, speak not and brand no motility, lest you break the spell." His manner was subdued, and his usual cockney vulgarity had entirely disappeared. I took the chair which he indicated, and awaited the result.

My companion cleared the rushes from the flooring in our neighbourhood, and, going down upon his hands and knees, described a half-circle with chalk, which enclosed the fireplace and ourselves. Round the edge of this one-half-circle he drew several hieroglyphics, not unlike the signs of the zodiac. He then stood upwards and uttered a long invocation, delivered so quickly that it sounded like a single gigantic discussion in some uncouth guttural language. Having finished this prayer, if prayer information technology was, he pulled out the small bottle which he had produced earlier, and poured a couple of teaspoonfuls of articulate transparent fluid into a phial, which he handed to me with an intimation that I should drink it.

The liquid had a faintly sugariness odour, not different the aroma of certain sorts of apples. I hesitated a moment before applying it to my lips, but an impatient gesture from my companion overcame my scruples, and I tossed information technology off. The sense of taste was not unpleasant; and, as it gave rise to no immediate effects, I leaned dorsum in my chair and equanimous myself for what was to come. Mr. Abrahams seated himself beside me, and I felt that he was watching my face from fourth dimension to time, while repeating some more of the invocations in which he had indulged before.

A sense of delicious warmth and languor began gradually to steal over me, partly, possibly, from the heat of the fire, and partly from some unexplained cause. An uncontrollable impulse to slumber weighed down my eyelids, while at the same time my brain worked actively, and a hundred beautiful and pleasing ideas flitted through it. So utterly lethargic did I feel that, though I was aware that my companion put his hand over the region of my heart, as if to feel how it were chirapsia, I did not attempt to prevent him, nor did I even ask him for the reason of his action. Everything in the room appeared to be reeling slowly round in a drowsy trip the light fantastic toe, of which I was the center. The great elk'due south caput at the far end wagged solemnly backward and forward, while the massive salvers on the tables performed cotillons with the claret-cooler and the epergne. My head fell upon my breast from sheer heaviness, and I should have become unconscious had I non been recalled to myself by the opening of the door at the other end of the hall.

This door led on to the raised dais, which, as I accept mentioned, the heads of the house used to reserve for their ain use. Equally it swung slowly back upon its hinges, I sat upward in my chair, clutching at the artillery, and staring with a horrified glare at the dark passage outside. Something was coming downward it — something unformed and intangible, but however a something. Dim and shadowy, I saw information technology waltz beyond the threshold, while a nail of ice-cold air swept down the room, which seemed to blow through me, chilling my very heart. I was enlightened of the mysterious presence, and then I heard it speak in a voice like the sighing of an east wind among pine-copse on the banks of a desolate sea.

Information technology said: "I am the invisible nonentity. I accept affinities and am subtle. I am electrical, magnetic, and spiritualistic. I am the bang-up ethereal sigh-heaver. I kill dogs. Mortal, wilt yard cull me?"

I was about to speak, just the words seemed to be choked in my pharynx; and, before I could get them out, the shadow flitted across the hall and vanished in the darkness at the other side, while a long-drawn melancholy sigh quivered through the apartment.

I turned my eyes toward the door once more, and beheld, to my astonishment, a very small onetime woman, who hobbled along the corridor and into the hall. She passed backward and frontward several times, and and then, crouching downwardly at the very edge of the circle upon the floor, she disclosed a confront the horrible malignity of which shall never be banished from my recollection. Every foul passion appeared to have left its marking upon that hideous countenance.

"Ha! ha!" she screamed, holding out her wizened hands like the talons of an unclean bird. "You meet what I am. I am the fiendish old woman. I wear snuff-coloured silks. My curse descends on people. Sir Walter was partial to me. Shall I exist thine, mortal?"

I endeavoured to shake my head in horror; on which she aimed a blow at me with her crutch, and vanished with an eldritch scream.

By this time my eyes turned naturally toward the open door, and I was hardly surprised to see a human walk in of tall and noble stature. His face was deadly stake, but was surmounted past a fringe of night hair which fell in ringlets down his dorsum. A short pointed beard covered his chin. He was dressed in loose-plumbing equipment apparel, made apparently of yellow satin, and a large white ruff surrounded his neck. He paced across the room with wearisome and majestic strides. And then turning, he addressed me in a sweet, exquisitely modulated vox.

"I am the cavalier," he remarked. "I pierce and am pierced. Hither is my rapier. I clink steel. This is a claret stain over my middle. I tin emit hollow groans. I am patronised by many former Conservative families. I am the original manor-house apparition. I work alone, or in visitor with shrieking damsels."

He bent his head courteously, equally though pending my reply, but the same choking sensation prevented me from speaking; and, with a deep bow, he disappeared.

He had hardly gone earlier a feeling of intense horror stole over me, and I was aware of the presence of a ghastly fauna in the room, of dim outlines and uncertain proportions. One moment it seemed to pervade the entire apartment, while at another it would become invisible, only e'er leaving backside information technology a distinct consciousness of its presence. Its voice, when it spoke, was quavering and gusty. It said: "I am the leaver of footsteps and the spiller of gouts of blood. I tramp upon corridors. Charles Dickens has alluded to me. I brand foreign and bellicose noises. I snatch letters and identify invisible hands on people'due south wrists. I am cheerful. I burst into peals of hideous laughter. Shall I exercise i now?" I raised my hand in a deprecating way, merely likewise late to forbid i discordant outbreak which echoed through the room. Before I could lower information technology the apparition was gone.

I turned my head toward the door in time to see a human being come up hastily and stealthily into the chamber. He was a sunburnt powerfully built fellow, with ear-rings in his ears and a Barcelona handkerchief tied loosely round his neck. His head was bent upon his breast, and his whole aspect was that of one affected by intolerable remorse. He paced quickly backward and forwards like a caged tiger, and I observed that a drawn pocketknife glittered in one of his hands, while he grasped what appeared to be a piece of parchment in the other. His voice, when he spoke, was deep and sonorous. He said, "I am a murderer. I am a ruffian. I hunker when I walk. I step noiselessly. I know something of the Spanish Primary. I can exercise the lost treasure business. I have charts. Am able-bodied and a skillful walker. Capable of haunting a large park." He looked toward me beseechingly, but before I could brand a sign I was paralysed by the horrible sight which appeared at the door.

It was a very tall man, if, indeed, it might be called a man, for the gaunt bones were protruding through the corroding flesh, and the features were of a leaden hue. A winding-canvass was wrapped round the figure, and formed a hood over the head, from under the shadow of which two fiendish eyes, deep set in their grisly sockets, blazed and sparkled like ruddy-hot dress-down. The lower jaw had fallen upon the breast, disclosing a withered, shrivelled tongue and 2 lines of black and jagged fangs. I shuddered and drew back as this fearful apparition advanced to the edge of the circle.

"I am the American claret-curdler," it said, in a vocalization which seemed to come up in a hollow murmur from the earth below it. "None other is genuine. I am the embodiment of Edgar Allan Poe. I am circumstantial and horrible. I am a depression-caste spirit-subduing spectre. Discover my blood and my basic. I am grisly and nauseous. No depending on artificial aid. Work with grave-apparel, a coffin-chapeau, and a galvanic battery. Plough hair white in a night." The animate being stretched out its fleshless arms to me every bit if in entreaty, only I shook my head; and it vanished, leaving a low, sickening, repulsive odour backside it. I sank back in my chair, so overcome by terror and disgust that I would have very willingly resigned myself to dispensing with a ghost altogether, could I take been certain that this was the final of the hideous procession.

A faint sound of trailing garments warned me that information technology was not so. I looked up, and beheld a white figure emerging from the corridor into the light. As information technology stepped across the threshold I saw that it was that of a young and beautiful woman dressed in the fashion of a foretime twenty-four hour period. Her hands were clasped in forepart of her, and her pale proud face diameter traces of passion and of suffering. She crossed the hall with a gentle sound, like the rustling of autumn leaves, and then, turning her lovely and unutterably sad eyes upon me, she said. "I am the plaintive and sentimental, the beautiful and ill-used. I have been forsaken and betrayed. I shriek in the night-time and glide down passages. My antecedents are highly respectable and generally aloof. My tastes are artful. Former oak furniture similar this would do, with a few more coats of mail and enough of tapestry. Will you not take me?"

Her voice died abroad in a beautiful cadence as she concluded, and she held out her hands as if in supplication. I am always sensitive to female influences. Too, what would Jorrocks's ghost exist to this? Could anything be in better taste? Would I not be exposing myself to the chance of injuring my nervous system by interviews with such creatures as my last visitor, unless I decided at once? She gave me a seraphic smile, every bit if she knew what was passing in my mind. That smile settled the affair. "She will do!" I cried; "I choose this one;" and equally, in my enthusiasm, I took a step toward her I passed over the magic circle which had girdled me round.

"Argentine, nosotros accept been robbed!"

I had an indistinct consciousness of these words being spoken, or rather screamed, in my ear a great number of times without my being able to grasp their meaning. A violent throbbing in my head seemed to accommodate itself to their rhythm, and I closed my optics to the lullaby of "Robbed, robbed, robbed." A vigorous milk shake caused me to open them over again, nonetheless, and the sight of Mrs. D'Odd in the scantiest of costumes and most furious of tempers was sufficiently impressive to recall all my scattered thoughts, and make me realise that I was lying on my back on the floor, with my head amongst the ashes which had fallen from last night's fire, and a small glass phial in my mitt.

I staggered to my feet, just felt so weak and lightheaded that I was compelled to fall back into a chair. Every bit my encephalon became clearer, stimulated past the exclamations of Matilda, I began gradually to recall the events of the nighttime. There was the door through which my supernatural visitors had filed. There was the circle of chalk with the hieroglyphics round the edge. At that place was the cigar-box and brandy-canteen which had been honoured by the attentions of Mr. Abrahams. But the seer himself — where was he? and what was this open window with a rope running out of it? And where, O where, was the pride of Goresthorpe Grange, the glorious plate which was to take been the delectation of generations of D'Odds? And why was Mrs. D. standing in the grey low-cal of dawn, wringing her easily and repeating her monotonous refrain? It was simply very gradually that my misty encephalon took these things in, and grasped the connection between them.

Reader, I take never seen Mr. Abrahams since; I take never seen the plate stamped with the resuscitated family unit crest; hardest of all, I take never caught a glimpse of the melancholy spectre with the abaft garments, nor do I wait that I always shall. In fact my night'southward experiences have cured me of my mania for the supernatural, and quite reconciled me to inhabiting the humdrum nineteenth-century edifice on the outskirts of London which Mrs. D. has long had in her heed's centre.

As to the caption of all that occurred — that is a matter which is open to several surmises. That Mr. Abrahams, the ghost-hunter, was identical with Jemmy Wilson, allonym the Nottingham crackster, is considered more than than likely at Scotland Thousand, and certainly the description of that remarkable burglar tallied very well with the appearance of my company. The pocket-sized bag which I have described was picked up in a neighbouring field next day, and institute to contain a option assortment of jemmies and eye-bits. Footmarks securely imprinted in the mud on either side of the moat showed that an accomplice from below had received the sack of precious metals which had been let down through the open window. No doubt the pair of scoundrels, while looking circular for a job, had overheard Jack Brocket's indiscreet inquiries, and promptly availed themselves of the tempting opening.

And at present as to my less substantial visitors, and the curious grotesque vision which I had enjoyed — am I to lay information technology down to any real power over occult matters possessed by my Nottingham friend? For a long time I was doubtful upon the point, and eventually endeavoured to solve it by consulting a well-known analyst and medical man, sending him the few drops of the so-called essence of Lucoptolycus which remained in my phial. I append the letter which I received from him, only too happy to take the opportunity of winding up my footling narrative by the weighty words of a human being of learning:

- "ARUNDEL STREET

- "Dearest Sir: Your very singular case has interested me extremely. The bottle which you lot sent contained a strong solution of chloral, and the quantity which you describe yourself as having swallowed must have amounted to at least eighty grains of the pure hydrate. This would of class have reduced y'all to a partial country of insensibility, gradually going on to consummate coma. In this semi-unconscious state of chloralism it is not unusual for coexisting and bizarre visions to present themselves — more particularly to individuals unaccustomed to the use of the drug. You tell me in your note that your mind was saturated with ghostly literature, and that you had long taken a morbid interest in classifying and recalling the various forms in which apparitions have been said to appear. Yous must also remember that y'all were expecting to see something of that very nature, and that your nervous organisation was worked up to an unnatural state of tension. Nether the circumstances, I think that, far from the sequel being an astonishing one, it would have been very surprising indeed to any one versed in narcotics had you non experienced some such effects. — I remain, dear sir, sincerely yours,

- "T. E. STUBE, M.D.

- "Argentine D'Odd, Esq. The Elms, Brixton."

- Back to Complete Works

- Back to Conan Doyle

Source: https://www.arthur-conan-doyle.com/index.php?title=Selecting_a_Ghost

0 Response to "Choking the Back of My Throat Then the Plume Appeared Again the Pyre by the Power of My Will"

Post a Comment